The American Dissident: Literature, Democracy & Dissidence

The Robert Creeley Award—Free Speech in Peril!

All prizes, like all titles, are dangerous. The seekers for prizes tend to labor not for inherent excellence but alien rewards: they tend to write this, or timorously to avoid writing that, in order to tickle the prejudices of a haphazard committee.

—Sinclair Lewis, “Letter to the Pulitzer Prize Committee”

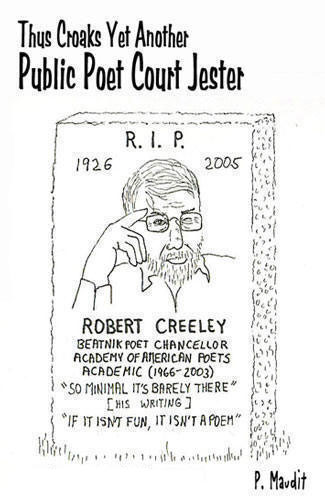

On three different occasions, I protested in front of Robert Creeley Award gala ceremonies in Acton, Massachusetts. It's not at all something I particularly enjoy. Who, after all, wants to look at a mob of poets and professors scorning democracy? The first time was in 2005 when I got to actually hand a broadside to C. D. Wright. In 2008, I got to see John Ashbery arrive surrounded by a protective buffer of poet worshippers. I didn't get to hand him a flyer. In 2010, it was beatnik, chancellor, tenured professor, zen buddhist Gary Snyder's turn to be anointed. The reason for my protesting against each of those poets was, not to get attention as the established order would like to believe, but rather because of their connection to the Academy of American Poets, which operates as an established-order censoring organization much like Poetry Foundation.

On three different occasions, I protested in front of Robert Creeley Award gala ceremonies in Acton, Massachusetts. It's not at all something I particularly enjoy. Who, after all, wants to look at a mob of poets and professors scorning democracy? The first time was in 2005 when I got to actually hand a broadside to C. D. Wright. In 2008, I got to see John Ashbery arrive surrounded by a protective buffer of poet worshippers. I didn't get to hand him a flyer. In 2010, it was beatnik, chancellor, tenured professor, zen buddhist Gary Snyder's turn to be anointed. The reason for my protesting against each of those poets was, not to get attention as the established order would like to believe, but rather because of their connection to the Academy of American Poets, which operates as an established-order censoring organization much like Poetry Foundation.

Foundations named after poets usually existed primarily to promote the poet in question and further his or her literary canonization. T-here is a certain selfishness about them, especially when created by friends and family. Of course Poet X was great; after all, I was married to him, etc., etc. Creating a non-profit organization also opens the doors to public funding.

Interestingly, tenured poet-professor C. D. Wright made well over $600,000 in 2005 from prizes and grant monies. What kind of nation would give that much money to a single poet, while nothing to so many others? I couldn't even get a $16 grant from the local Concord Cultural Council for The American Dissident, publishing in Concord since 1998 (See www.theamericandissident.org/CCC.htm). Why not? For one thing, cultural councils tend to award grants to projects that entertain and otherwise divert attention from corruption. The following are my accounts of the C. D. Wright and John Ashbery protests, as well as a little essay on the Robert Creeley Award. For my account of the Snyder anointment, see my blog entry at wwwtheamericandissidentorg.blogspot.com/2010/03/fierce.html.

The C. D. Wright Protest

At about 6:30, I arrived in front of the Acton Town Hall, put on my poet parrhesiastes placard around my neck to attract attention to the protest, and stood ready with flyers in hand.

DEMOCRACY NEEDS POET PARRHESIASTES, NOT PULITZER COURT JESTERS

POETRY NEEDS TO BE MORE THAN DIVERSIONARY ENTERTAINMENT

My first flyer went to a teenage blond with mother straggling 20 feet behind. “You here for poetry?” I asked. “Yes,” she said. “Well, take one,” I said. Then a stern short woman came barreling out the door: “Hello. I’m one of the people in charge of this.” “Hi, take a flyer,” I said. She seemed a bit confused, not sure what to do or say, so grabbed a flyer and walked back inside. A young tall black-haired woman approached me, introducing herself as Sylvie, took a flyer and hung around for a few minutes, asking what poets I liked and mentioning she was all for free speech. “Well, that’s unique for a poet,” I said. “No, it’s not,” she said. “From my experience, it sure as hell is,” I said. I mentioned Francois Villon. She’d never heard of him. “I’m starting tonight,” she said, which meant she was going to read her poems. Whoopee! It seemed mostly an older and friendlier crowd than the one at the Concord Poetry Center. I tried my best not to be intimidating, though there was just so much one could do. “Thank you very much,” I’d reply after each flyer hand out. Only a few eventually attempted to read my placard and not one of them had ever heard of the word parrhesiastes, so I explained. “It’s more than a word. It’s an ancient Greek tradition where poets and others would dare speak rude truth to power.” As each person approached the front doors (and me), I’d repeat, “I’m protesting poetry!” They seemed to like that because it brought humor to the situation. For most, it was just impossible to fathom poetry as an object of protest. The general look was of surprise. “Why?” a few hazarded to ask. “Well, you’ll have to read the flyer to find out,” I’d say. C. D. Wright arrived. I wondered how much she was getting for the reading and Creeley prize. “I am happy to be able to hand it to you personally,” I said. “I hope I got the likeness right.” She seemed confused, suddenly confronted not by fawners but by unexpected protest. “No personal animus intended,” I said. “Why not share some of the wealth?” “Okay,” she said, entering the building. I was happy to know she knew almost everyone in her audience would have my flyer and cartoon effigy of her. It made it all worthwhile. “You look like you knew Robert Creeley,” I said to an older guy. “Well, actually I did,” he said. “Well, don’t shoot me,” I said handing him flyer number two with Creeley cartoon. “What’s the alternative, Jerry Springer?” he said entering the building. “Well, that’s a good point,” I said. “I’ll have to consider it.” A young woman approached but refused to take a flyer. “I was the one with the cellphone outside the last time you protested in Concord,” she snapped. “I remember you!” I said. “You’re a Concord Poetry Center bureaucrat, right?” She entered the building without response. The ones that killed me were the stern-faced males, poets most likely, so functionary in manner, who really looked like they hated me. But they were far and few between that evening.

My first flyer went to a teenage blond with mother straggling 20 feet behind. “You here for poetry?” I asked. “Yes,” she said. “Well, take one,” I said. Then a stern short woman came barreling out the door: “Hello. I’m one of the people in charge of this.” “Hi, take a flyer,” I said. She seemed a bit confused, not sure what to do or say, so grabbed a flyer and walked back inside. A young tall black-haired woman approached me, introducing herself as Sylvie, took a flyer and hung around for a few minutes, asking what poets I liked and mentioning she was all for free speech. “Well, that’s unique for a poet,” I said. “No, it’s not,” she said. “From my experience, it sure as hell is,” I said. I mentioned Francois Villon. She’d never heard of him. “I’m starting tonight,” she said, which meant she was going to read her poems. Whoopee! It seemed mostly an older and friendlier crowd than the one at the Concord Poetry Center. I tried my best not to be intimidating, though there was just so much one could do. “Thank you very much,” I’d reply after each flyer hand out. Only a few eventually attempted to read my placard and not one of them had ever heard of the word parrhesiastes, so I explained. “It’s more than a word. It’s an ancient Greek tradition where poets and others would dare speak rude truth to power.” As each person approached the front doors (and me), I’d repeat, “I’m protesting poetry!” They seemed to like that because it brought humor to the situation. For most, it was just impossible to fathom poetry as an object of protest. The general look was of surprise. “Why?” a few hazarded to ask. “Well, you’ll have to read the flyer to find out,” I’d say. C. D. Wright arrived. I wondered how much she was getting for the reading and Creeley prize. “I am happy to be able to hand it to you personally,” I said. “I hope I got the likeness right.” She seemed confused, suddenly confronted not by fawners but by unexpected protest. “No personal animus intended,” I said. “Why not share some of the wealth?” “Okay,” she said, entering the building. I was happy to know she knew almost everyone in her audience would have my flyer and cartoon effigy of her. It made it all worthwhile. “You look like you knew Robert Creeley,” I said to an older guy. “Well, actually I did,” he said. “Well, don’t shoot me,” I said handing him flyer number two with Creeley cartoon. “What’s the alternative, Jerry Springer?” he said entering the building. “Well, that’s a good point,” I said. “I’ll have to consider it.” A young woman approached but refused to take a flyer. “I was the one with the cellphone outside the last time you protested in Concord,” she snapped. “I remember you!” I said. “You’re a Concord Poetry Center bureaucrat, right?” She entered the building without response. The ones that killed me were the stern-faced males, poets most likely, so functionary in manner, who really looked like they hated me. But they were far and few between that evening.

“Are you Tod Slone?” asked a man with accompanying son. “The guy who did this?” “Yeah, that’s me,” I said. “Do you have a website where I can buy a copy of the magazine?” he asked. “Is it on this paper?” “Yes,” I said, doubting I’d ever hear from him. A woman stepped out and approached me angrily. She was the same size as me. “Robert Creeley’s widow is upstairs crying right now because of this!” she loudly berated me, waving my Creeley cartoon. “Well, it wasn’t my purpose to upset her,” I said. “I didn’t know she was going to be here.” She planted herself a foot away from my face, threateningly and continued reprimanding me. “I believe in most of what you say on the flyer, but this isn’t right!” she said. “What you’re saying then is I shouldn’t express my opinion because I might end up upsetting someone’s widow,” I said. “That’s not democracy.” “I’m not saying that at all,” she said. “Well, what are you saying then?” I asked. “Look, I’m Martin Espada’s wife!” she said. “Robert Creeley really helped us a lot! His widow is upstairs now very upset because of this!” “Ah, I did a cartoon on Martin Espada a little while ago with a heart on his sleeve saying ‘I Love Creeley’,” I said. “It’s MartEEEn,” she said, “not Martin!” “Como quieras,” I said. “No me importa. Martin, si quieras.” We rapped in Spanish a little. Her kid was next to me, my size, looked like he was 16, and potentially angry, if not violent. Espada’s wife told me she’d brought him with her so he could see… me or her in action or both of us, I wasn’t sure. During the conversation, Concord Poetry Center director Joan Houlihan arrived. “Oh, I thought you were part of Concord Poetry Center,” she said, smirking and guffawing. “You did?” I said. “Is that me in the cartoon?” she asked. “No, it’s someone else,” I said. “I can’t put you in all the cartoons, but you’re definitely in the text.” “Oh, that’s so cute,” she said snidely with grin. “How smug of you,” I said. She entered. “See, that’s what I’m protesting!” I said to Espada’s wife. “On the one hand she says how much she loves dissident poets, and on the other she mocks me because I’m dissident. She’s the CEO of the Concord Poetry Center. Did you read what she said in my flyer? If you protest at our opening, you can’t teach protest poetry at our center.” “Yes, it is sad,” said Creeley’s wife, who then rapped about how corrupt the whole poetry scene was. “Creeley really helped Martin get tenure,” she said. “Everyone else wanted to get rid of him because he does speak out.” “Well, that’s positive,” I said. “My opinions are definitely flexible. But that’s what I’m talking about. Who is Creeley anyhow? Is he some kind of god, who gets to choose which one gets tenure and which doesn’t, which poet is good and which one isn’t?” She can sort of see my point… but not entirely… because she is personally involved. “He was a friend for 20 years,” she said. “He didn’t sell out.” “Oh, no?” I said. “So he wasn’t like Ginsberg, pushing his friends all the time and settling into Brooklyn College as a tenured crony.” To my surprise she agreed with me on Ginsberg. “Aren’t you trying to change things?” she asked. “No, not at all,” I said. “I don’t believe they can be changed short of a violent revolution.” “Then why are you doing this?” she asked. “I’m simply exercising my First Amendment rights in a public place,” I said. “Or you could consider me as someone like Houlihan prefers to see me as an angry man, protesting to inflate the ego, and desperately attempting to get recognized. But, hey, I’m not angry and how the hell am I going to get recognized doing this shit here in Acton?” She laughed. “We should be together on this, not against each other,” I said. “My purpose was never to upset Creeley’s widow. I didn’t know he was even married. I thought he was a homosexual.” “Creeley was so good because he helped Martin when they were both at Naropa,” she said. “What an indoctrinating crap hole that is,” I said. She eventually warmed up and told me how poor she and Martin were. “We only have $700 in the bank,” she said. “How can that be possible,” I said. “Your husband’s a tenured academic at U. Mass.” “He was offered $1200 to speak in the Midwest but it was sponsored by Coke so he refused to take the money,” she said. “They told him not to drink Coke when he speaks. In Columbia, Coke is killing all these people. Well, I better get back inside now, he’s going to be introducing her.” “That’s precisely what I’m talking about,” I said. “One academic backslapping another.” “Well, I promise I’ll email you,” she said. “We have to continue this discussion.” I never heard from her again… or anyone else who’d taken a flyer.

The John Ashbery Protest

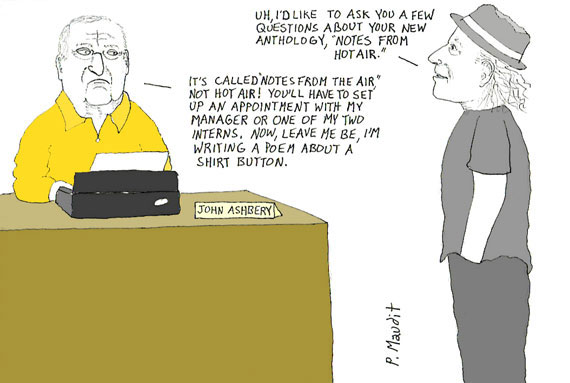

First I drove to Staples to make 35 copies of the broadside at 9 cents each (no grant for that or anything else!), then by 6:45 in the evening I found myself standing outside in front of the Junior High School in Acton where poet John Ashbery would be reading at 7:30. I wore my "No Dissident Poetry" sign around my neck and began handing out flyers. It was a bit cold but bearable. My first flyer went to an old man parked in a handicapped spot. Lots of people arrived but mostly to take night courses. I quickly learned to discern between those holding books and those without (the poets!In about 10 minutes the cops pulled up (two cars!). One officer got out and approached me.

First I drove to Staples to make 35 copies of the broadside at 9 cents each (no grant for that or anything else!), then by 6:45 in the evening I found myself standing outside in front of the Junior High School in Acton where poet John Ashbery would be reading at 7:30. I wore my "No Dissident Poetry" sign around my neck and began handing out flyers. It was a bit cold but bearable. My first flyer went to an old man parked in a handicapped spot. Lots of people arrived but mostly to take night courses. I quickly learned to discern between those holding books and those without (the poets!In about 10 minutes the cops pulled up (two cars!). One officer got out and approached me.

“Have I broken a law?” I asked.

“No, we had a call that you were forcing pamphlets on people,” he said.

“Can I ask who called?” I asked.

“We can’t say,” he said.

“Well, I’m not forcing anything on anyone,” I said. “I’m just standing here.”

“Okay, I’m just checking,” he said.

They were intimidating. That was their job. I knew what they were capable of, having been arrested and incarcerated before, though I'd broken no laws at all. In any case, a couple of young yuppie-corporate looking sporty fellows in blazers walked by, the new generation of poets? They didn't want a flyer. They’d just come to listen to Ashbery. Another cop walked into the building and gabbed with the busybody concierge who I could see constantly looking at me through the window. Had she lodged the complaint? “You’re a beacon!” said another young yuppie looking character with girl attached to his side. “Everyone knows where the poetry is cause you’re here!” “Democracy and poetry!” I said to the fellow. “Well, I can see you’re interested.” He refused to take a flyer. It is sad to witness the incuriosity of poets and citizens in general.

One of the cop cars remained planted 10 feet away from me. “Democracy and poetry, an oxymoron!” I said. "Democracy and poetry at work, very rare indeed.” The poets were young and old, and most evidently could not fathom my message at all. “Oh, I’m an Ezra Pound fan,” said an older professorial-appearing black man. Evidently, he couldn’t fathom it either. “Have a good night,” said the cop walking back out of the building. “You too,” I said. He must have explained to the concierge—they were chatting for a long time—that I was not breaking the law. One of the young yuppie fellows in blazer stepped back out to smoke a cigarette. He sat on the bench about 20 feet across from me. “So, what’s your method?” he asked. “Guns and knives,” I said, knowing damn well he didn’t give a damn. He asked a few more innocuous questions, and I asked why he was asking questions, if he wasn't really interested and didn't even want to take a flyer. His response was nothingness.

The grand prize-winner John Ashbery finally arrived, quite diminutive and rotund, surrounded by a tightly packed coterie, protective buffer, as if he were the president and they the FBI. They quickly ushered him past me. I had no intention of hassling the old fellow. “JOHN ASHBERY DOESN'T CENSOR ANYBODY," bellowed a middle-aged woman (Bob Clawson would later inform that she was Pen Creeley). “WELL HIS ACADEMY OF AMERICAN POETS CENSORED ME, LADY," I bellowed back. Not one of them would take a flyer. “DEMOCRACY TAKES VIGOROUS DEBATE!" she bellowed as she ran away from vigorous debate. They'd all entered the building before I could even respond. They must have known I’d be present… and that was good. “Poetry and protest,” I said to newcomers. "Poetry and protest!" “No, we don’t want to protest poetry!” said a middle-aged man with female attached to his side. “Then you don’t think!” I responded. They entered the building. I left at 7:35, having no desire whatsoever to listen to the evening's celebrity poet. Back at the house I poured a glass of red, and watched the Doris Duke Story with Fiennes and Sarandon.

Literature, Democracy, Money, Fame, and an Indoctrinated Citizenry

Let your life be a counterfriction to stop the machine.

—Henry David Thoreau

I am ashamed to think how easily we capitulate to badges and names, to large societies and dead institutions.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Vigorous debate is the cornerstone of democracy! Yet Acton librarians scorn it just as they do the American Library Association’s Bill of Rights, which states that “libraries should provide materials and information presenting all points of view on current and historical issues.” Acton librarians have, for example, outright rejected my contrarian viewpoints on the Robert Creeley Poetry Award and Academy of American Poets , sponsor of National Poetry Month. The Academy, by the way, censored my opinions from its website. John Ashbery was a chancellor of the Academy. Do you think he gives a damn about that censorship incident? Of course he doesn’t! Do you give a damn? My experience tells me you likely don’t. Thus is the American democracy today! The Acton-Boxborough library literary committee equally shuns vigorous debate, as do most poets and academics, including those backing the annual Robert Creeley Poetry Award.

We must cease encouraging students to worship fame, literary or whatever! Instead, we must teach them to question and challenge it! John Ashbery got famous and “eminent” by not making waves in the conformist academic sea, not going against the literary grain, not rocking the established-order boat, not risking his career and otherwise not manifesting the courage to “go upright and vital, and speak the rude truth in all ways” (Emerson). Question: How can one possibly be “controversial” (see Wikipedia entry on Ashbery), while at the same time known for writing “playful verse,” much appreciated by established-order poets? Answer: Simply not possible! Fame is an orchestrated diversion set in motion by the wealthy to divert the minds of citizens away from the grave concerns of democracy… and they are doing a damn good job at it!

The Robert Creeley Poetry Award has been accorded to one established-order “safe” poet after the next. There is no reason at all to be proud about it. Poets receiving it have been tenured, careerist academics lacking the courage to buck the system that stuffs their bellies so nicely. Creeley himself was thus! Should we be proud of them or him, while democracy continues accelerating in a downward spiral into the toilet bowl? The Robert Creeley Foundation will only end up “mythifying” Creeley, turning him into something greater than he was. It will serve to indoctrinate local students. Instead, we should be showing those students what the Beatniks became—cocooned careerist professors and exclusive club members of the Society of American Poets, for the most part, pumping hot air into their own myth. Yes, “feted with numerous awards”! But citizens in a democracy need to think and not behave as blind admirers of award recipients. Again, what do those awards tend to signify more than anything else? They signify that recipients played the game and dared not counter it. Bob Clawson, founder of the Creeley Award, boasts that attendance at the Ashbery event will be high because of “an apparent hunger to hear poets of the quality and fame we’ve chosen over the past eight years.”

Contrary to the opinion of established-order cogs like Clawson , “quality” is by no means an objective trait. We must cease teaching students the contrary and stop indoctrinating them in the established-order bourgeois literary canon. We must, for the sake of democracy, teach them to question and challenge all things, including the canon and literary prizes. We must teach them to examine who the judges of those prizes are, what connections they may have with the recipients, etc. We must teach them that money is perverting and diluting everything in America , including poetry. Well-endowed foundations (e.g., Poetry Foundation has over $125 million) are determining more and more what poetry shall be praised and what poetry shall be buried. Clearly, poetry daring to evoke that very fact will be buried. Poetry questioning and challenging the Creeley Award will also be buried.

Clawson has anointed himself judge of “talent”! “We offer talented young poets a discerning audience and gain the opportunity to reach out to neighboring communities.” Sadly, however, his definition of “talent” is one that will likely not rub the wealthy the wrong way and one that will not question and challenge the literary social order. “We’re spreading the word,” he proclaims. But what “word” is he spreading, if not the innocuous one that dares not upset the local pillars of the community! How does spreading Clawson ’s “word” help democracy? On the contrary, it can only harm it…