The American Dissident: Literature, Democracy & Dissidence

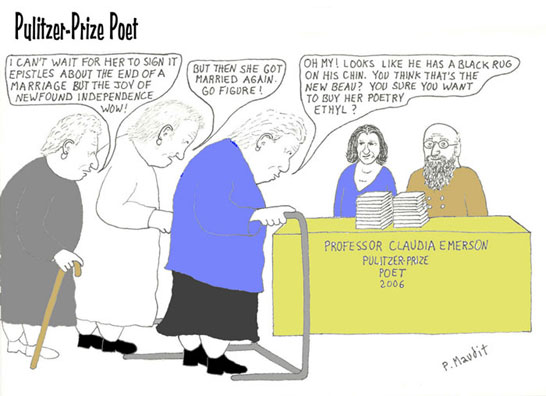

The Pulitzer Prize

Between the Pulitzer Prizes, the American Academy of Arts and Letters and its training-school, the National Institute of Arts and Letters, amateur boards of censorship, and the inquisition of earnest literary ladies, every compulsion is put upon writers to become safe, polite, obedient, and sterile. In protest, I declined election to the National Institute of Arts and Letters some years ago, and now I must decline the Pulitzer Prize.

—Sinclair Lewis, “Letter to the Pulitzer Prize Committee” (examine the entire letter.)

It is unfortunate that our teachers and professors do not educate us to think, question and challenge. Instead, they inform us that so and so won the Pulitzer Prize, and, just like them, expect us to be immediately awe-stricken. Rare is the teacher or professor who may push us to question what in fact constitutes the Pulitzer, who in fact are the Pulitzer judges, and who in fact tend to be the Pulitzer recipients. Rare is the teacher or professor who may have his or her students read Sinclair Lewis’ “Letter to the Pulitzer Prize Committee.” By chance and intellectual curiosity, rather than from the recommendation of one of my many teachers or professors, I discovered that letter.

It is unfortunate that our teachers and professors do not educate us to think, question and challenge. Instead, they inform us that so and so won the Pulitzer Prize, and, just like them, expect us to be immediately awe-stricken. Rare is the teacher or professor who may push us to question what in fact constitutes the Pulitzer, who in fact are the Pulitzer judges, and who in fact tend to be the Pulitzer recipients. Rare is the teacher or professor who may have his or her students read Sinclair Lewis’ “Letter to the Pulitzer Prize Committee.” By chance and intellectual curiosity, rather than from the recommendation of one of my many teachers or professors, I discovered that letter.

What is the most prestigious literary prize in America? It is the Pulitzer, created in 1904 by Joseph Pulitzer, scion and newspaper publisher, and consists today of a $5000 award granted in 21 different categories, including journalism and literature. The subjective term “distinguished” is used to characterize winning recipients. The Pulitzer endowment created Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, which runs the Pulitzer Prize. For this year, 102 judges were selected, each designated “distinguished.” It is difficult to determine what percent of those judges were liberal, conservative, multimillionaire or politically correct without an in-depth analysis. My hypothesis is that most of them were probably well to do, disconnected from the reality of those not enjoying the economic boom, and from the general reality of whistleblowers, nonconformists, and dissidents. The Columbia Journalism Review revealed that for the 1999 Prizes, 66 of the judges were men and only 17, women. It did not reveal racial profiles, nor profiles of degree of conformity or dissidence.

What is the most prestigious literary prize in America? It is the Pulitzer, created in 1904 by Joseph Pulitzer, scion and newspaper publisher, and consists today of a $5000 award granted in 21 different categories, including journalism and literature. The subjective term “distinguished” is used to characterize winning recipients. The Pulitzer endowment created Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, which runs the Pulitzer Prize. For this year, 102 judges were selected, each designated “distinguished.” It is difficult to determine what percent of those judges were liberal, conservative, multimillionaire or politically correct without an in-depth analysis. My hypothesis is that most of them were probably well to do, disconnected from the reality of those not enjoying the economic boom, and from the general reality of whistleblowers, nonconformists, and dissidents. The Columbia Journalism Review revealed that for the 1999 Prizes, 66 of the judges were men and only 17, women. It did not reveal racial profiles, nor profiles of degree of conformity or dissidence.

Roughly 2000 entries were filed this year, surprisingly few, especially considering the vast network of egomaniacal American poets seeking such prizes and permitted to apply themselves as long as one book of poetry published during the application period. Well, the fee to apply is $50, certainly enough to keep unemployed and homeless poets from applying.

The judges, or more democratic-sounding term, jurors, as the Columbia School prefers to call them are divided into groups: poetry, novel, political commentary, photography, drama, etc. Each group sends their top three choices to the Pulitzer board, which consists of 20 “leading” journalists, authors, and scholars, who select the ultimate winners. Who are these “leading” persons?

The board members for this year included 14 CEO newspaper publishers and editors, five academics, including the President of Columbia University, dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University, chairperson of the Department of Journalism at Boston University, a Harvard University professor of Humanities, and one administrator. This, of course, doesn’t even represent a viable sample of academics, let alone of the rest of the writing populace.

Regarding the Pulitzer Prize winners for poetry, my brief analysis sought to determine whether or not any patterns existed and included the past six winners. Data for years prior to 1995 is not currently available on the Pulitzer web site. I have not examined the content, nor style of the Prize poetry. Perhaps that will constitute a future analysis.

In any case, C. K. Williams was this year’s winner and an academic, teaching in the Creative Writing Program at Princeton University. All three of his judges were English professors, one of whom was actually at Princeton University, the very same institution as the winner. Blatant conflict of interest? I definitely think so… but surely the Pulitzer authorities would think otherwise and be able to rationalize or even deny any such conflict.

Mark Strand, winner of the1999 Pulitzer, was also an academic, teaching at the University of Chicago. He was also a former Poet Laureate of the United States, thus in good standing with the Library of Congress and politicians. Two of his jury members were English professors, the third president emeritus of the Poetry Society of America. Strand was also a recipient of grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and Guggenheim Fellowship, organizations, which ought also be examined under independent lens.

Charles Wright, winner of the 1998 Pulitzer, was an academic teaching English at the University of Virginia. Two of his jury members were English Professors, the third, editor of the Southern Review. Now, why didn’t the Pulitzer organization choose the editor of The American Dissident to serve on the jury? Wright was also a recipient of grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and Fulbright lecturer. One must wonder whether those organizations may be interconnected. Do they share the same board members and who are the members? These questions must be posed and answered.

Lisel Mueller, winner of the 1997 Pulitzer, was as close to being an academic as possible, without officially being an academic, as a visiting writer at several academic institutions, including the University of Chicago and Washington University. All three of her jury members were English professors, one of whom was a previous Pulitzer Prize winner. Mueller was also a Pushcart Prize winner, another “prestigious” prize which I am currently analyzing.

Jorie Graham, winner of the 1996 Pulitzer, was an academic, teaching in the Writers' Workshop at the University of Iowa. All three of her jurors were English professors. She was also a recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship. Philip Levine, winner of the 1995 Pulitzer, was a lifetime academic. Two of his jurors were English professors; the third, a Souder Family professor, whatever that is.

As mentioned, details for years prior to 1995 are not currently available on the Pulitzer website (www.pulitzer.org). Nevertheless, it is likely that winners and their selecting juries were similarly ‘controlled’ by Academe. It is also important to mention that the Pulitzer’s deliberations, much like Academe’s deliberations, have always been secret, and judges have always refused to publicly debate or defend their decisions, some of which have been evidently quite questionable, including the refusal of Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls and Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? The latter was determined insufficiently “uplifting.” Clearly, the Pulitzer will not be awarded to hardcore critics of Academe and writers of intrinsic academic corruption. It will never be awarded to poets who criticized any of the Pulitzer establishment/organization figures for the simple reason that Academe loathes critics of Academe. Given statistics, the Pulitzer will most likely not be awarded to nonacademic poets. Yet why should poets who enjoy lifetime job security and generally easy lives be assumed to be better poets than those living on the edge as poètes maudits à la Rutebeuf, Villon, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Verlaine?

In conclusion, George Orwell brilliantly stated in his essay, “The Prevention of Literature:” “There is no such thing as genuinely nonpolitical literature, and least of all in an age like our own, when fears, hatreds, and loyalties of a directly political kind are near to the surface of everyone’s consciousness. Even a single taboo can have an all-round crippling effect upon the mind, because there is always the danger that any thought which is freely followed up may lead to the forbidden thought.”

Clearly, those “fears, hatreds, and loyalties” exist widespread today throughout Academe and are reflected in the Pulitzer establishment/organization. Personally, I have smelled them and felt the absolute, ugly brunt of them on numerous occasions. Clearly, the egregious “taboo” for academic poets and writers is: don’t criticize the hand that feeds, that is, Academe and its literary establishment. Clearly, that taboo gravely affects the writing of academics, who, rarely, if ever, criticize academic journals, literary prizes, and academe’s dubious meshing with local politicians and corporations.

It is more than apparent that academics have come to define the best poetry as verse written by academics because they monopolize the judgeships of the most prestigious literary award in America, the Pulitzer Prize. Corporations and politically-controlled cultural councils have increasingly ‘purchased’ academics to the extent that perhaps the Corporation and Politician now determine the very nature of poetry designated as the best (e.g., must be “uplifting”). Even the Pulitzer, which was in dire need of funding in the 70s, had to resort to the creation of a second endowment fund, no doubt funded by corporate donors. The close ties between academics, corporate CEOs and politicians have become more and more evident today. Clearly, the nefarious result of such connections, regarding poetry, has been the widespread disengagement of verse. Indeed, in America, politicians readily invite poets to dinner, whereas in countries such as Spain, the former Soviet Union, Yugoslavia and China, they assassinated, jailed and, otherwise, viscerally hated them.

Students of literature need to be fully educated regarding the patent political/academic/corporate connection. The Pulitzer must be advertised as an academic Prize, not as an absolute Prize. The same must be said with the Guggenheim Fellowships, Fulbright lectureships, Pushcart Prize, and National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) grants. People on the boards of such institutions tend to be politically connected if not outright appointed. Regarding the NEA, for example, the Center of Public Integrity noted in its publication, The Public I, that “The Grossmans have contributed at least $400,000 to the Democratic Party and to Clinton since 1991. In 1994, Clinton appointed Barbara Grossman, who is a professor of theater at Tufts University, to the National Council for the Arts.”

Evidently, poets who are not academics and who criticize academe, politicians, their cultural councils, and literary establishments will never be recipients of the Pulitzer. Students must be taught that those institutions and the cloistered men and women adorning black robes and tasseled hats, who in reality simply define academic poetry, should not alone be ordained to define great poetry. Perhaps, Columbia University needs to reflect on these matters. Unfortunately, pushing its face into them will probably not be possible. Would its Columbia Journalism Review publish this essay or consider a proposal for such an essay? Well, here’s Assistant Editor Lauren Janis’ response:

The editors read with interest your proposal for an article that would analyze how and why the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry is an inherently unfair contest. It is an intriguing idea, and your arguments certainly piqued the interest of our editors. Yet, as we are not a poetry publication, after consideration, we decided it wasn’t right for CJR. Thank you for your interest in our magazine.