The American Dissident: Literature, Democracy & Dissidence

The National Endowment for the Arts—Free Speech in Peril

Literature should not be suppressed merely because it offends the moral code of the censor.

—Chief Justice William O Douglas

The selector begins, ideally, with a presumption in favor of liberty of thought; the censor does not. The aim of the selector is to promote reading not to inhibit it; to multiply the points of view which will find expression, not limit them; to be a channel for communication, not a bar against it.

—Lester Asheim, “Not Censorship but Selection” (Wilson Library Bulletin, 1953)

All censorships exist to prevent anyone from challenging current conceptions and existing institutions. All progress is initiated by challenging current conceptions, and executed by supplanting existing institutions. Consequently, the first condition of progress is the removal of all censorships. There is the whole case against censorships in a nutshell.

All censorships exist to prevent anyone from challenging current conceptions and existing institutions. All progress is initiated by challenging current conceptions, and executed by supplanting existing institutions. Consequently, the first condition of progress is the removal of all censorships. There is the whole case against censorships in a nutshell.

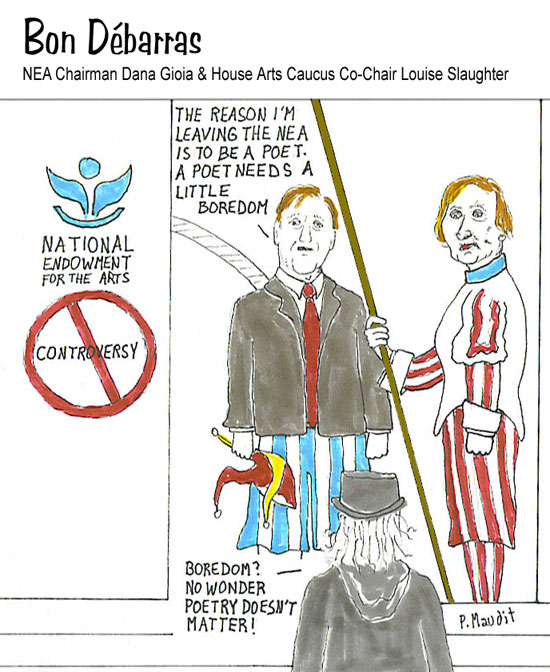

—George Bernard Shaw

The National Endowment for the Arts operates as one of a number of modern-day LITERARY CENSORING ORGANIZATIONS akin to the Catholic Church of yesteryear which put together the Index Librorum Prohibitorum. It has been periodically criticized since its creation in 1965. Will Obama's NEA be any different than Bush's Dana Gioia NEA? Probably not. Will Frankel, Peede, and Stolls still be firmly entrenched in the organization? Probably. Gioia had been adept at gaining the support of Republicans and Democrats on the House Arts Caucus (imagine what kind of ear-marked art, poetry and literary journals the caucus sought and seeks to push). He has a "talent for management and for handling controversy," noted the Honorable Louise Slaughter (D-N.Y.), one of the Caucus co-chairs. Imagine, a talent for management! Just what we needed in the arts and literature. Imagine, a talent for handling controversy! But how much talent does it take to slam the door shut on it, as it did with The American Dissident? Democracy continues its downward spiral thanks in part to the democracy-indifferent literary managers of the NEA.

"He had incredible ideas for everyone on how to sell themselves [sic]," said the Caucus co-chair regarding Gioia. "It was absolutely astonishing." Yes, tell us about it. Astonishing! Management, kill controversy, and teach artists how to sell themselves. For the NEA, one fundamental question remains explicitly unstipulated and explicitly unanswered: what constitutes “artistic excellence” in literature? Submitting literature that fits into the implicit response to that question (e.g., not apt to upset the literary status quo and in that sense not apt to upset the academic determiners of literary icons and canon) is the key to obtaining a literary grant from the NEA, which must therefore be intrinsically at odds with the key to creating powerfully honest writing. Clearly, some sort of unanimity exists amongst NEA cultural functionaries (Democrat and Republican) with regards "good taste" and "artistic excellence."

"He had incredible ideas for everyone on how to sell themselves [sic]," said the Caucus co-chair regarding Gioia. "It was absolutely astonishing." Yes, tell us about it. Astonishing! Management, kill controversy, and teach artists how to sell themselves. For the NEA, one fundamental question remains explicitly unstipulated and explicitly unanswered: what constitutes “artistic excellence” in literature? Submitting literature that fits into the implicit response to that question (e.g., not apt to upset the literary status quo and in that sense not apt to upset the academic determiners of literary icons and canon) is the key to obtaining a literary grant from the NEA, which must therefore be intrinsically at odds with the key to creating powerfully honest writing. Clearly, some sort of unanimity exists amongst NEA cultural functionaries (Democrat and Republican) with regards "good taste" and "artistic excellence."

This essay follows in the critical tradition and might rightfully be perceived as possessing an angry tone, which in the realm of bourgeois literati inevitably constitutes the "wrong tone" and "bad taste." In any case, my outrage stems not so much from being rejected for a government grant, but rather from the refusal of public grant-according functionaries to accord me, a common citizen publisher, precise criticism with supporting evidence. It also stems from the realization that such functionaries are likely (inevitably) inbred, dogmatic, and closed-minded to dissident points of view. Jon Parrish Peede, Director of Literature for the NEA, for example, smugly dismissed my questions and criticisms as “mere rants.” That of course would not have surprised Solzhenitsyn in the least, that is, if Peede had instead been Secretary of the Union of Soviet Writers.

Such ad hominem (rants inevitably come from "ranters") seems sadly to have become typical in the milieu and indicates, more than anything else, an uncanny inability to logically respond to tough critique. For example, this essay was sent to Guernica, a left-leaning literary journal, blurbed by Howard Zinn, which oddly publishes interviews by established-order Library of Congress poet laureates, including Pinsky, Kooser, Collins, and Hass. Joel Whitney, one of its two editors, responded: “We don't do rants, which is what your piece reads like to me. It's really self-involved and paranoid.” Oddly, he perceived nothing aberrant regarding his interview with Billy Collins, who stated unabashedly with regards poet laureates: "Suddenly you're asked to stop looking at specifics—I mean, I write about saltshakers and knives and forks—and talk like a politician.” Well, evidently, I don’t write about saltshakers, nor do I talk like a politician (left or right), thus surely I must be “blinded by ego and rage.” In vain, I brought that anomaly to Whitney’s attention.

Such ad hominem (rants inevitably come from "ranters") seems sadly to have become typical in the milieu and indicates, more than anything else, an uncanny inability to logically respond to tough critique. For example, this essay was sent to Guernica, a left-leaning literary journal, blurbed by Howard Zinn, which oddly publishes interviews by established-order Library of Congress poet laureates, including Pinsky, Kooser, Collins, and Hass. Joel Whitney, one of its two editors, responded: “We don't do rants, which is what your piece reads like to me. It's really self-involved and paranoid.” Oddly, he perceived nothing aberrant regarding his interview with Billy Collins, who stated unabashedly with regards poet laureates: "Suddenly you're asked to stop looking at specifics—I mean, I write about saltshakers and knives and forks—and talk like a politician.” Well, evidently, I don’t write about saltshakers, nor do I talk like a politician (left or right), thus surely I must be “blinded by ego and rage.” In vain, I brought that anomaly to Whitney’s attention.

In any case, possessing a doctorate and having taught 20 years full time as a university professor in both France and the USA, I am not a fool and know the NEA is likely as unaccountable as perhaps most other public organizations in America. Just the same, I thought at least I’d bring that notion, if not observation, to the NEA’s attention and otherwise test the waters of democracy, something I’ve enjoyed doing over the past several decades.

The categorical dismissal by NEA panelists of The American Dissident, the literary journal the editor created a decade ago, ought to be disturbing because the journal’s prime intent is to offer a unique forum for vigorous debate, cornerstone of democracy, sadly shunned by the bulk of the nation’s literary journals (see, for example, LiterarySurvey), including those supported by the NEA year after year after year (e.g., Ploughshares, Agni, Threepenny Review, and Kenyon Review). The American Dissident also focuses on examining the dark side of the academic/literary established order, characterized not by openness and desire for debate, but rather by rife backslapping, cronyism, intellectual conformity, self-vaunting a la www.danagioia.net, and unoriginal “good taste.” The editor has been periodically, if not constantly, perfecting the journal for over a decade. It is not cheaply produced and does not publish anything and everything. In fact, it rejects outright the type of “good taste” literature filling the pages of the journals typically accorded NEA grants. In other words, it seeks to offer something different and encourage criticism in the milieu. In fact, it seeks to publish poems that actually risk something on the part of the poet, be it job, speaking invitations, grants, sabbaticals, future publications, or whatever. Sadly, few poets risk anything in their verse, rendering their output entirely safe for the consumption of corrupt pillars of society. The American Dissident seeks to raise the general status of poet as laureate seeker to parrhesiastic truth teller. Only then might the poet truly obtain respect from the citizenry… and political leadership.

From the NEA's damning comments (see below), one might obviously conclude the panelists to be card-carrying members of the established order. Since the NEA is a public organization, however, it should be held to open its doors to those evidently not of that milieu. The NEA is a colossus of free public money, but apparently only for those who do not question and challenge it. Since it is a public entity, however, it must be held accountable and must provide equal opportunity for grants to rare organizations that actually do challenge it. Its staff and panelists need to be educated in the importance of dissidence and vigorous debate for any thriving democracy and literature itself.

To apply for an NEA grant, I spent a generous $400 gift from a former subscriber to become a 501 c3 nonprofit organization. A year after my application, a tedious process indeed, I received a form-letter rejection. It took another month to finally squeeze out a half-ass response from Director of Literature Jon Parrish Peede as to why precisely the journalhad been denied funding. If I had known in advance the NEA would be entirely intolerant to criticism of it and of the general academic/literary established order, The American Dissident would not have become a nonprofit literary journal. If the NEA had been honest and upfront, the editor would have been spared the tedious waste of time.

Since the money and time were already spent, however, I thought perhaps the NEA owed me, as a citizen, an explanation why it refused to accord The American Dissident a grant. It is a travesty for its panelists to offer such scant, unhelpful feedback:

The artistic merit of the publication is low; the design and readability of the publication is [sic] poor.

With regards “design and readability” (and I’m assuming “readability” refers to the physical not to the intellectual, though for lack of information I could be wrong), the NEA awards grants, year after year, to Rain Taxi, for example, which is a rather cheaply produced newspaper-format publication. Its design is as uncreative as it gets, and the publication is stuffed with business advertisements. Is the design of The American Dissident “poor” because it includes no such advertisements? The ink used for printing The American Dissident does not rub off in ones fingers like that used to publish Rain Taxi. As for other usual grant suspects (e.g., Ploughshares, Agni, Threepenny Review, and Kenyon Review), who can even tell the difference between them? What makes their design meritorious, while that of The American Dissident “poor”? The latter offers unusual and creative rubrics (e.g., “Experiments in Free Speech,” “Activist Broadside,” “Dissident Poems from the Dead,” "Panem et Circenses," and “Literary Letters”), while they do not. It also offers front cover illustrations that actually say something, as opposed to fancy artistic vacuity. But it also tries to maximize the quantity of writing on each page, thus likely contains less empty space, and probably uses smaller font sizes, for it does not possess ample NEA-accorded funds to create capacious issues. In any case, the NEA to date simply refuses to be specific and otherwise helpful.

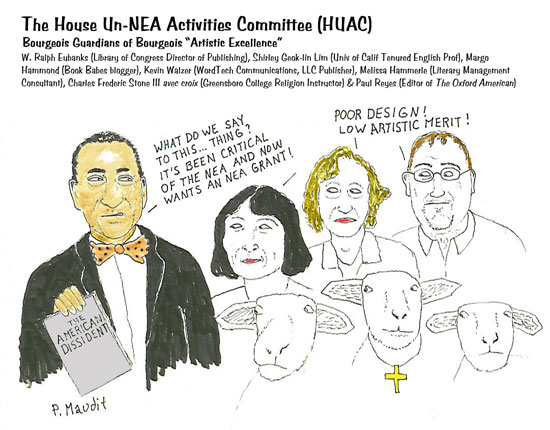

With regards “artistic merit,” how did NEA panelists unanimously conclude “low” for The American Dissident? How indeed to interpret their very unanimity? And what might their definition of “artistic merit” be? For wont of any other explanation, business as usual, or rather literature as usual, likely served as their sole criterion. Evidently, that most vague and damning feedback (i.e., “low”) was meant not to encourage, but to highly discourage the journal from ever applying for a government grant again. After all, how could such a general comment ever help me to “improve” it in the eyes of NEA functionaries? Clearly, that feedback indicates The American Dissident struck a “political” and, in Salman Rushdie’s words, “disrespectful” nerve with the panelists—each and everyone of them. Likely, that constitutes the very reason why the NEA chooses not to be honest and upfront. In other words, unlike the usual suspects which tend to be politically correct (multicultural brouhaha ad nauseum) and have pro-status-quo literary stances, The American Dissident is highly politically-incorrect, even somewhat anarchistic, and boasts a clear anti-status-quo literary position. It is probable for that very reason the panelists chose to dismiss it as “low” and “poor.” In other words, since the panelists conveniently fail to illustrate convincingly (or even minimally) their conclusions, what else is one to believe? But shouldn’t panelists be held to support their conclusions with concrete examples? When I teach writing courses, always I insist my students back any statements made with examples—the more damning the statements, the more examples! Lack of accountability can only explain why the panelists conveniently avoid doing that and get away with it. Despite my requests, the NEA to date has only provided a response to the first of the following questions posed regarding its panelists:

1. Who precisely were the panelists who made the comments regarding The American Dissident?

2. What precisely are their educational backgrounds and aesthetic preferences?

3. Why were there no “dissident”-leaning panelists at all on the deciding committee; in other words, panelists critical of the current literary scene, literary icons, and canon in general?

4. Were panelists connected in any way whatsoever to award recipients?

5. Are there regulations against such connections?

6. How does one obtain a position as panelist?

7. How might I become a “dissident” panelist—a breath of fresh air—for the NEA?

8. Do panelists, in the name of democracy and vigorous debate, make a conscious effort each year to accord funding to a literary journal apt to go against the NEA grain? If not, why not?

By the way, similar questions were also posed, in vain, to literary apparatchiks of the Massachusetts Cultural Council. See the footnote below for that exchange. My questions were apparently tough ones because they were first posed to Amy Stolls, NEA Literary Specialist, who then handed them over to her boss, Director of Literature Peede, who finally handed them over to his boss, Robert H. Frankel, Acting Deputy Chairman for Grants & Awards. The latter sent me the list of panelists, “Access to Artistic Excellence Literature Panel A.” A thinking citizen would of course immediately ask: what precisely constitutes “Artistic Excellence”? A thinking citizen would also ask why the NEA does not present a definition of this highly nebulous and thus subjective term. When I queried Peede with that regard, he simply chose not to respond and acted indignant as if the asking of such a question were in itself impolite.

On the Internet, I hunted for information (and photos for future satirical cartoons) on the seven panelists, who unanimously designated The American Dissident as “low” and “poor,” expecting no surprises whatsoever. In other words, the likelihood was overwhelming that each one of them was well inserted into the academic/literary established-order milieu of absence of questioning and challenging... of that milieu. Indeed, I could find nothing at all that could even remotely indicate a slight critical streak or minute dissension with bourgeois society in general—they were, each and every one of them, literary apparatchiks incarnate. W. Ralph Eubanks, Director of Publishing Library of Congress Washington, DC, is an Afro-American who likely did not appreciate my criticism of the poet laureates designated by his employer, the Library of Congress. Melissa Hammerle, former Director of New York University Creative Writing Program, “now consulting with a wide range of literary organizations, conferences, and programs,” likely disdained my critiques of academics and other literary managers like herself. Margo Hammond, featured in GoodHousekeeping.com as co-blogger of Book Babes, which seeks “to nurture fellowship around the love of books,” is a book editor of the St. Petersburg Times. “The Book Babes recommend books to help find happiness in life”... enough to make a thinking poet-citizen vomit, right?!

Shirley Geok-lin Lim, Malaysian born, is tenured professor in the English Department at the University of California, Santa Barbara. I suspect she didn’t care much for my cartoons mocking the tenured elite. In fact, I sent this essay to over 20 members of that department. Not one deigned to respond. After all, team-playing and collegiality have become the cancerous plague of the university today... with regards truth.

Paul Reyes is editor of The Oxford American, a glossy-coveredlit journaldevoted to not offending the southern bourgeoisie and to bolstering the literary established-order. Charles Frederic "Rick" Stone III (Layperson), not to be confused, I suspect, though I could be wrong, with Charles Richard Stone, civilly committed patient in the Minnesota Sex Offender Program, is instructor of religion at Greensboro College. Surely, he must have seethed at my criticism of organized religions, especially with regards Bennett College (Greensboro, NC).

As for Kevin Walzer, the last of the panelists, he runs “Public Poetry,” a website devoted to poetry that does not make waves, that does not incite vigorous debate, that does not, in a nutshell, serve the public at all... with the exception of helping it to sleep at night. He is also publisher of WordTech Communications, LLC—is he a Brit or simply another tax evader? “We are unique among contemporary poetry publishers for the emphasis we place on bringing poetry to a buying audience—in short, for the emphasis we place on selling books. We are focused solely on publishing and selling excellent poetry.” Sell, sell, sell, anything but truth, truth, truth! Surely, he must have hated The American Dissident because its mantra is clearly the opposite of his. And again, what constitutes “excellent poetry”? How I detest that term, for it inevitably signifies “bourgeois,” and usually not much else. By the way, this essay was also sent to each panelist, as well as Gioia, Frankel, Peede, and Stolls. Unsurprisingly, the response has been nil. It was also sent to The American Scholar. However, I dared criticize Joseph Epstein, one of its former editors. Epstein, emeritus instructor of Northwestern University, had rightly argued: “I think it fair to say that one of the first qualifications of an American poet laureate is that he not in any way be dangerous.” However, he became immediately indignant when I stated “I think it fair to say that one of the first qualifications of an American emeritus instructor is that he not in any way be dangerous either.”

The general consensus and bias in the academic/literary established-order milieu is that political poetry is rarely if ever good poetry. How many times have I heard and read that cliché from bourgeois literati? And how easy to counter it: apolitical poetry is rarely if ever good poetry! The subjectivity involved in both statements ought to render them null and void. Unfortunately, the established-order milieu wields the power (money) and with that power manages to void the latter while propagating the former. In any case, what recourse do I have, as a common American citizen-editor? With regards The American Dissident, the legality of a public-grant funding organization to reject it on the basis of political content must be questioned. What I need therefore is pro-bono legal assistance. And I haven’t the slightest idea where to obtain it. Evidently of lesser importance, the panelists also noted a few problems with my proposed budget calculations:

The reach of the publication is limited (only 50 subscribers), though you are printing 4,000 for three issues, the budget is incorrect (submitted figures incorrect), specifically: ‘the total other expenses’ line under direct costs summary line was blank; the ‘total direct costs’ summary line was incorrect (had the figure for the above line).

It seems wrong to be able to dismiss a grant application on budget miscalculations or other simple errors when panelists could easily email an applicant to ask for precision or correction. However, the proposed budget for The American Dissident was clearly calculated to pay for a distributor, which requires a minimum 1,000 copies per issue. Why didn’t panelists therefore understand my budgeting for 4,000 copies? The chief reason I applied for an NEA grant was to get money to increase the circulation of The American Dissident. By the way, one of the usual NEA-grant-accorded suspects, the politically-correct Small Press Distribution, refuses to help in that endeavor. It takes a lot of time and effort to fill out an NEA application. Panelists don’t seem at all sensitized to that fact. Just the same, it is more than evident The American Dissident was rejected not for budget errors, but rather for political reasons. As for the “reach of the publication” being “limited,” I am left wondering if that comment was meant to be deprecatory. Since when does popularity necessarily indicate good or great literature?

The NEA policy of granting thousands of public dollars, year after year, to the same organizations, which really don’t even need the money,* must be reassessed and not by wealthy MBA-businessmen of the Dana Gioia and John Barr (Poetry Foundation) ilk. The NEA needs to cease according thousands and thousands of public dollars, year after year, to Threepenny Review, Kenyon Review, Ploughshares, Agni, American Poetry Review, Poetry Flash, ZYZZYVA, Cave Canem, Calyx, Dalkey Press, Copper Canyon Press, Curbstone Press, Graywolf Press, Feminist Press, Milkweed Editions, Poets & Writers, Inc., Alice James Books, and Small Press Distribution. How not to wonder if NEA decision-making panelists might be connected to those entities in some manner or other! And such dubious connections have certainly occurred in the past (e.g., Underground Literary Movement documented an incident where novelist Jonathan Franzen was accorded a grant by a panel chaired by Rick Moody, a friend of

his.). “Sunlight is the most powerful of all disinfectants,” argued Justice Brandeis. Yet NEA panelists and selection thereof remain clothed in darkness.

One must also wonder why the NEA continues to grant thousands of dollars to well-endowed universities and colleges that happen to sponsor literary reviews, including University of Massachusetts, University of Nebraska, University of Hawaii, Bard College, Antioch University, Boise State University, Boston University, and Wesleyan University.* Why does it accord, year after year, thousands of dollars to the Academy of American Poets, which favors censorship of anyone daring to question and challenge it (see AAP), as opposed to dissidence and vigorous debate? Why does it accord grants to Poets & Writers, Inc., which also acts as censor, filtering out uncomfortable opinions and refusing to list journals like The American Dissident? Why does it accord thousands of dollars, year after year, to Poetry Society of America which shuns debate and ignores criticism? Ah, but some of the thousands will be used to place placards of innocuous poetry in public transportation systems around the country. Wouldn’t the nation be better served, however, if those placards were placed in public restrooms instead? Why does the NEA, a public organization, fund religious organizations, including the Center for Religious Humanism, Young Men's Christian Association, Young Men's & Young Women's Hebrew Association, and Southern Methodist University, whose Southwest Review—the NEA notes—will be publishing an entire politically-correct issue to "modern fiction from Arabic women"? Will the fiction be any good? Or doesn’t that even matter in the multicultural mindset?

Finally, without precision, how can I, a mere unconnected citizen-editor, ever be able to alter The American Dissident in an effort to have it fit into the acceptable-status-quo mold of Ploughshares, Agni, and Kenyon Review, for example, without simply copying them? Must I beg to become a member of the NEA-funded Council of Literary Magazines and Presses—which does not accept all journals applying for membership—, requisite for enrolling in a members-only, how-to-get-an-NEA-grant workshop, presented by Amy Stolls, NEA Literary Specialist? How not to smell the stink of conflict of interest in that situation? The reality, of course, is that if the focus of The American Dissident, workshop or not, remains the same, established-order panelists will unanimously refuse to accord it grants.

The NEA is a giant Cyclops with the one-eyed vision of business-as-usual literature, in other words, safe wit, highbrow metaphor, tedious obfuscation, and obligatory political correctitude—in a nutshell, bourgeois. Shouldn’t it be its job, as a public institution, however, to encourage new applicants, especially those daring to “go upright and vital, and speak the rude truth in all ways” (Emerson) with its regard and literature in general? Shouldn’t it, as a democratic institution, logically be encouraging The American Dissident with concrete advice, including suggestions for literary re-education? Instead, the reality of the NEA is its shameful reluctance to debate those who dare question and challenge it. Robert H. Frankel, Acting Deputy Chairman for Grants & Awards, sums that up in his final letter to me:

Finally, please be advised that by this response all pertinent information concerning your rejected application specifically and the NEA panel review process generally has been provided to you. Agency staff will not engage in further correspondence with you on these matters.

In other words, “low” and “poor” is the only real feedback NEA literary functionaries are willing to accord. Unfortunately, logic tends to be ineffective with regards such apparatchiks and their public organizations. Solzhenitsyn knew that. “Acceptance by government of a dissident press is a measure of the maturity of a nation,” had written Justice William O. Douglas. Clearly, something was once quite rotten in Denmark and the Soviet Union, while today the rot of immaturity is evident in the heart of America’s National Endowment for the Arts.

………………………………………………………..

*Some of the NEA usual suspects (e.g., Agni and Ploughshares) also receive thousands from the Massachusetts Cultural Council each year. Boston University, a private institution, which has over one billion dollars in endowment funds, is home to Agni. Why indeed should taxpayers be funding Agni? It seems that few artists and writers ask questions any more. Thus, I posed the question to Charles Coe, Program Coordinator. His response, an unsurprising avoidance response, was the following:

The MCC grants funds to Agni because the review panel determined that the publication met the program criteria of quality, community benefit and fiscal and administrative management.

What, however, are the criteria defining “quality”? How has “quality” been objectified? The term “artistic excellence” is the trump card—often, if not always—played by cultural functionaries. After all, how can a common citizen possibly contest the indefinable? Dan Blask, Program Coordinator for the MCC, argued regarding my query as to whether or not the MCC would be open to highly critical themes:

You asked about themes. The emphasis in this review is not on particular themes but on artistic excellence. All grant decisions for the Artist Fellowships Program are based solely on artistic quality and creative ability, as demonstrated by the work submitted.

Yes, “artistic excellence”! In other words, you’ll know it when you see it, read it, sniff it, though especially when one of our functionaries tells you that you have it or don’t. Just the same, I pushed on and asked Blask what precisely were the criteria for making determinations with regards the evidently subjective designation "artistic excellence"? Without having a clue with that regard, how could I, after all, possibly determine whether or not what I had to offer might fall even remotely within the realm of "artistic excellence"? Clearly, certain themes must inevitably, no matter how they are treated, be deemed by official cultural apparatchiks as lacking “artistic excellence.” Likely, “artistic excellence” is rarely, if ever, accorded to themes critical of the academic/literary established-order milieu, including public cultural councils. Blask’s response was the following:

We convene a panel of accomplished artists, critics, presenters, and other arts professionals to make grant decisions, and each panelist decides for him- or herself what constitutes artistic excellence. It is a subjective decision. In an effort to make the process as fair as possible, we make sure that the panelists represent a wide variety of expertise and perspectives.

Thus, Blask replaces one subjective concept with another, “accomplished,” which in reality signifies degree of popularity within the milieu. But how can one possibly be popular (i.e., “accomplished”) within the milieu, if one is an ardent critic of it? That is the crux of the quandary. In other words and to the detriment of democracy, critics of the milieu need not apply for public grants because the milieu dispenses them. My final letter to Blask queried if ever the MCC possessed literary panelists, who openly questioned and challenged (or even whose work focus was open questioning and challenging) the cultural institutions making determinations with public monies and questioning and challenging the canon itself and those who seek to bolster and propagate it. Clearly, if the MCC did not regularly have such panelists, it was likely that anything I submitted would be deemed not of “artistic excellence.” Blask’s response avoided the question:

Since we rely on panelists solely for their artistic opinions, when selecting them we focus on their artistic expertise and accomplishments, rather than on particular views or beliefs. If you have any potential panelists you’d like to suggest, please pass them along to me.

Needless to say, I proposed myself as a potential panelist. In vain, I'd done that with the local Concord Cultural Council about five years ago. Yes, I'd filled out the little form at Town Hall. But the local politicians are the ones who make the final determinations. And I've been outwardly critical of the local Chamber of Commerce, which supports the local politicians. To date, I haven't heard a thing. Silence is usually the best weapon of those in power. In any case, I pushed Coe and Blask for precision as to why taxpayers funded Agni and Harvard University Museums, for example, when both organizations were connected to private billion-dollar corporate educational institutions and why the MCC only funded literary journals that did not NEED the funding? The American Dissident, based in Massachusetts, has yet to receive a dime from the MCC because it does not possess the minimum amount of money required to even apply. “A literature organization must have a budget of $10K to apply,” replied Coe. So, why, I asked, did the MCC establish the $10K minimum-budget rule, if not to exclude literary journals with limited funds and why would such journals necessarily not merit funding? Coe, evidently tiring of my questions, simply avoided responding:

I already pointed out the basis on which decisions to fund an organization are made. Sorry if that answer doesn’t satisfy you.

As for Blask, he suggested I contact his boss, Director of Grant Programs Mina Wright who, after I contacted her, suggested I drive into Boston, pay the high parking fees, and meet with her regarding my questions. I told her I’d agree to it if she helped with the parking and offered me a job as literary panelist. She has yet to respond. Evidently, she is not going to respond because she disdains vigorous debate, preferring the comfort of inbred pol-connected and pol-correct autocracy. Clearly, something is rotten in the hearts and minds of public grant-according bureaucrats. Theirs has become an impenetrable wall of bricks mortared together not with truth but with managerial team playing, networking, and careerism, a wall that a simple citizen can never hope to breach. Nonetheless, I will continue hammering away at that fraudulence. Below is the email sent to Wright. Were the questions too difficult for her to answer… or simply too damning if answered?

Dear Mina Wright, Director of Grant Programs:

Mr. Dan Blask, Program Coordinator, has been helpful with regards certain questions I’ve posed, though only to a certain extent. (Mr. Charles Coe, Program Coordinator, simply ceased responding.) Mr. Blask thus suggested I contact you regarding them, as well as implicit suggestions:

1. Why do taxpayers fund Agni and Harvard University Museums, for example, when both organizations are connected to private billion-dollar corporate-educational institutions? Does this not indicate something rotten in the very hearts and minds of grant-according panelists and in the MCC in general?

2. Why does the MCC only fund literary journals that don’t really need the funding? In other words, why does a journal with a budget under the necessary $10K minimum not even merit consideration for funding? As editor of The American Dissident, a highly unique literary journal devoted to unusual vigorous debate, cornerstone of democracy, I cannot even get funding from the local Concord Cultural Council. Nothing! And I’ve been trying for a decade!

3. Why does the MCC rarely, or perhaps never, have as panelists individuals whose very creation is focused on hardcore criticism of the academic/literary established-order milieu and canon itself? If a project highly dissident in nature with such a focus were to be presented before established-order type panelists, evidently it would immediately be deemed not of “artistic excellence.” Don’t you agree? After all, it would take a rare panelist who could look at criticism of the panelist him or herself… and actually proceed objectively.

4. Mr. Block stated: “Since we rely on panelists solely for their artistic opinions, when selecting them we focus on their artistic expertise and accomplishments…” Since “accomplishments,” however, inevitably translates as popularity in the established-order milieu, doesn’t that rule for obtaining panelists preclude someone with a dissident outlook and focus (i.e., someone not popular in the milieu, thus not “accomplished”)?

5. Since the MCC is a public organization, should it not make a special effort to open its doors not simply to multicultural viewpoints, but to dissident political viewpoints as well? Would that not benefit democracy, as opposed to literature as usual in the status-quo oligarchy?

Clearly, these are tough questions without simple answers. For democracy, however, they demand answers. How might I become a dissident panelist for the MCC? Despite the uphill battle, I have been published (e.g., a 170-pp bilingual French/English poetry book published by Gival Press 2008), possess a doctoral degree from the Université de Nantes (France), and when employed have worked as a professor. The only thing I’m missing are political and literary connections, the very connections that are taking the bite out of American literature. Thank you in advance for your responses.

This essay has been revised numerous times. With further information, it will be revised yet again and again. MCC apparatchiks were informed of its existence. Not one of them responded with its regard. Who knows, perhaps one of the NEA panelists might actually seek dialogue. Miracles do happen… or so they say.