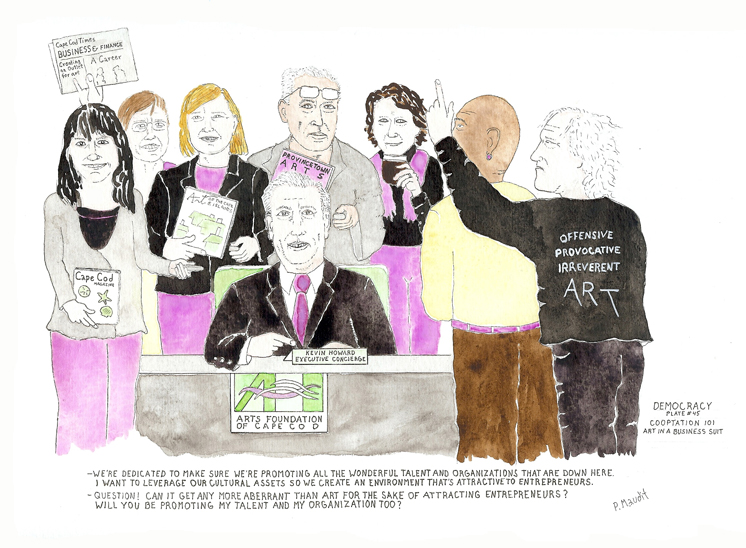

The American Dissident: Literature, Democracy & Dissidence

Provincetown Arts

Christopher Busa, Founding Editor. Annual Issue 2006/07. Magazine format. 160 pp. US $10.00. Provincetown, MA. cbusa@comcast.net

The cover of this very slick, very expensive magazine is a painting of a naked young man holding an umbrella and dog eating or licking his hand. Perhaps that sums up Provincetown Arts. The painting is by Tony Vevers, whose paintings are influenced by the touchstone poems of Yeats. The full painting is reproduced on page 36 and is of three naked white men, one carrying a dead deer on his back, three dogs and another dead deer lying on the beach. Other Vevers’ paintings are also reproduced in glossy color and include more naked men, women, and dogs. Not my cup of tea—maybe yours?

The cover of this very slick, very expensive magazine is a painting of a naked young man holding an umbrella and dog eating or licking his hand. Perhaps that sums up Provincetown Arts. The painting is by Tony Vevers, whose paintings are influenced by the touchstone poems of Yeats. The full painting is reproduced on page 36 and is of three naked white men, one carrying a dead deer on his back, three dogs and another dead deer lying on the beach. Other Vevers’ paintings are also reproduced in glossy color and include more naked men, women, and dogs. Not my cup of tea—maybe yours?

The table of contents and masthead appear after no less than 30 pages of glossy advertisements (e.g., pizza pie, jewelry, motels, galleries, and universities), the last of which lists the magazine’s money donors and awards received. The Massachusetts Cultural Council is one such donor. It has systematically refused to help fund The American Dissident, a Concord-based literary journal because, amongst other reasons, it will only fund magazines with an annual budget of at least $10,000. In other words, only magazines that have plenty of money can even apply for cultural grants from the MCC! Advertisements abound throughout the magazine leading one to believe it must rake in thousands of dollars in such revenues. As for the prizes, they include Best American Poetry and Pushcart Prize.

Provincetown Arts is indeed a big organization including seven board of directors and nine board of advisors, including poet Stanley Kunitz, who died this past year. Its The focus is, according to the editor, “the community of artists and writers [one must assume of means] whose “physical locus (is) in Provincetown,” a very, very expensive neighborhood, where the likes of Norman Mailer own homes. PTown is also known for its sizeable gay community.

The art featured in Provincetown Arts is entirely, one can safely say, socio-politically disengaged and bourgeois in aspect and spirit. In fact, it might be implied that engaged art and writing are prohibited from its pages. Jim Peters’ displays several paintings of naked women on a few pages after Vevers, while Penelope Jencks several sculptures of naked women after that. Of interest, perhaps, is the account, “Notes of Another Nude Model,” by Kathleen Rodney, author of Reading with Oprah. Yikes! “The year is just three days old, and I am starting it by standing naked as a newborn in front of three middle-aged men I have just met.” Then Ken Vose writes a two-page essay on “Marilyn Art,” that is, hackneyed Marilyn Monroe as subject of painters. Ugh.

The editor, Christopher Busa, writes a lengthy book review of Thrown Rope by artist Peter Hutchinson. He admires not only the latter’s art but also his “facility with language” and terminates the review with Hutchinson’s writing on the letter W and “how it stands for Writing.”

While watching winter wane,

Wanda wondered, “Would

Warren wait?” “When Woonsocket

Worries women, what would

Wisconsin win?” Warren writes

Wednesdays, welcoming wrestling.

“What wonderful wrecks,”

Wanda wailed. “Wishes whitewash

Wisdom.”

Need I comment on that piece of wonder and wisdom? But surely it does reflect on the very slick shallowness of Provincetown Arts. Another review by Tracey Anderson, “De Kooning’s bicycle: Artists and Writers in the Hamptons,” pushes the hollow myth of celebrity artists… who drank. Ugh. Aberrantly, one can read a long three-page hagiographic article on the artist Nancy Webb… written by her son Patrick Webb. Am I dreaming? Unfortunately, I am not.

The Art Talk rubric contains commentaries from roughly 50 artists. I skimmed through most of them and could not find one artist at war with society. Recall James Baldwin’s statement: “The obligation of anyone who thinks of himself as responsible is to examine society and try to change it and to fight it—at no matter what risk. This is the only hope society has.” Well, if the artists in Provincetown Arts are representative of the general herd of artists, we can be assured that American society has little hope. Denny Camino’s statement sums up the social concern of the 50 featured artists: “My art is engaged with the space it occupies.”

Fred Marchant’s “The Sense of an Ending” on Gail Mazur’s new chapbook collection is yet another example of egregious hagiography, or backslapping in layman’s terms. His essay acts as an oversized blurb. To be fair, Edith Kurzweil’s essay on William Phillips, “A Partisan Memoir,” is of interest. In it we learn how Phillips was indeed a radical in spirit. Unfortunately, however, Kurzweil does not inform us how the radical Partisan Review ended up so established-order and Phillips going to “dinner parties in Provincetown.” Her essay is another example of hagiography.

Jason Shinder’s essay on “Howl” is yet another example of base hagiography, pushing of lit icons, and unquestioning allegiance to the established-order lit milieu. What about the new Howls? The ones poets are in fact writing today? Nobody’s interested in them. Hell, I could give you a hundred of mine… or several hundred from other poets I know. But the likes of Shindler and Busa simply desire to push the old myths. The new poets of Howls would likely frighten them away. Why doesn’t Shindler ask what happened to the author of “Howl”? How could someone who wrote that poem end up so easily co-opted into the corporate university? I suppose we could blame that university for Shindler’s seeming unwillingness or inability to pose such an evident and pertinent question.

Need I comment on the poems in the back of the magazine penned by 15 poets? No surprise there at all… of course. Diane Thiel’s “When they threw me in the river/ I sank to the bottom, then rose/ to the surface—a swan” sums them up nicely. Ugh. Where is the passion, the fight, the conflict with power in those poets? Where is their Socratic daemon? They all must lead such easy comfy co-opted lives.

Provincetown Arts clearly supports the assertion that the arts in America are determined by the wealthy, which is probably why there are so many painters painting politically-harmless naked men and women. It clearly represents the very worst of art and writing in today’s America—self-laudatory, backslapping, and absolutely nothing critical of the art and writing milieus. How could I possibly recommend it?

—The Editor